A Shifting Alliance : Bangladesh’s Defence Turn Towards Pakistan

Once bitter rivals, Pakistan and Bangladesh are now moving toward an unexpected defence partnership. Under an unelected interim government, Dhaka is distancing itself from New Delhi and warming to Islamabad. This shift — marked by joint exercises and possible arms deals — signals a bold realignment of Bangladesh’s identity and could reshape South Asia’s strategic balance.

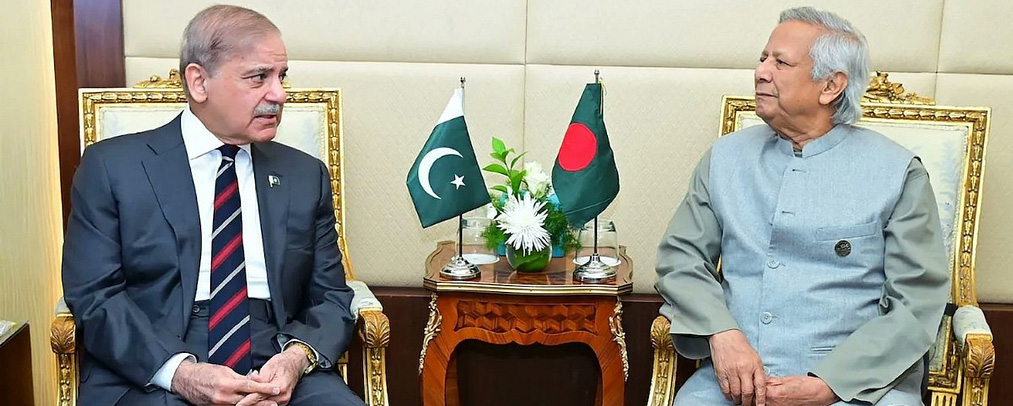

Once at war with one another, the armies of Pakistan and erstwhile East Pakistan — modern-day Bangladesh — are keen to partner with each other in defence cooperation. Under the interim government led by Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus, Bangladesh’s foreign policy is taking a direction that stands in stark contrast to its history of fraught relations with the country from which it won independence in 1971. In its fifty-five years of existence, Dhaka has generally maintained a distance from Islamabad. Relations warmed considerably between 2001 and 2006, when a coalition of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Jamaat-e-Islami governed the country. The subsequent return of the Awami League to power in 2009, led by Sheikh Hasina and bearing the legacy of her father, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman — a pillar of the Liberation War against Pakistan — re-established minimal diplomatic interaction with Islamabad. As the Awami League remained in office for the next fifteen and a half years until last August, this practice became a near-permanent feature of Bangladesh’s governance. However, as rising discontent against the Awami League led to Prime Minister Hasina’s ouster, the interim government has deliberately begun to diverge from “Awami traditions” to forge a new national identity — one that consciously distances itself from the country’s historical and geographical realities.

Exchanges and Exercises

Over the past few months, there have been several defence exchanges between Pakistan and Bangladesh, signalling a thaw in bilateral ties. In January alone, two notable interactions took place between the defence personnel of both countries. The first meeting took place in two parts. On 14 January, a Bangladeshi military delegation led by the Principal Staff Officer of the Bangladesh Armed Forces Division, Lieutenant General SM Kamrul Hasan, met General Syed Asim Munir, Pakistan’s Chief of Army Staff and General Sahir Shamshad Mirza, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee, at the Pakistani General Headquarters in Rawalpindi. The next day, Lt. Gen. Hasan met Air Chief Marshal Zaheer Ahmed Baber Sidhu, Chief of the Pakistan Air Force, at Air Headquarters in Islamabad. Both sides discussed regional security dynamics, the scope for joint military exercises, training programmes, and defence trade.

Later in the month, a military delegation led by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) Director General, Major General Shahid Amir Afsar, visited Dhaka to meet their Bangladeshi counterparts. This was one of the first high-level engagements between the ISI and Bangladeshi officials in decades, aimed at strengthening military and intelligence cooperation. In February, Dhaka’s warship BNS Samudra Joy participated in a naval exercise, Aman-25, hosted by Islamabad in the northern part of the Arabian Sea, off the coast of Karachi. Besides Bangladesh, the multinational event included navies from 120 countries, including three of India’s neighbours: Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and China.

The Changing Narrative

Addressing the Aman Dialogue 2025, the Bangladesh Navy Chief, Admiral Mohammad Hasan, underscored the importance of the military exercise, saying, “Land divides but sea unites.” This statement echoes a comment made earlier in the year by the Pakistani military, which alluded to the two nations as “brotherly countries” that must remain “resilient against external influences.” The phrasing is geopolitically significant and represents a notable turn in the established historical narrative of bilateral differences. It comes amidst talks of Pakistani promises to train the Bangladesh Army and Dhaka’s reported interest in acquiring JF-17 Thunder fighter jets from Pakistan to upgrade its military assets under its “Forces Goal 2030”. Jointly developed by Beijing and Islamabad, these jets symbolise a potential trilateral defence partnership between China, Pakistan and Bangladesh — particularly as Beijing is the largest defence partner of both countries and is involved in arms transfer and infrastructure development. As per the latest available data, 81 percent of Islamabad’s (2020-2024) and 73.6 percent of Dhaka’s (2010-2020) imported weaponry was sourced from China.

As the data verifies, China has been Bangladesh’s largest defence partner since the Hasina administration. However, over the past decades, Dhaka pursued a “diplomacy of balance” in its engagement with India and China, which enabled it to effectively navigate major power politics, aligning with its national interests while maintaining its autonomy. That balance has become lopsided in recent months, with ties straining between Dhaka and New Delhi over multiple issues, including the shelter of the former PM Hasina in India. In the purview of defence, Bangladesh has reportedly invited Chinese investment to develop an airbase at Lalmonirhat, near India’s strategically sensitive Siliguri Corridor — which connects the politically fragile Northeast to the rest of the country — without regard for New Delhi’s sensitivities.

Dhaka’s recent outreach to Islamabad is further shifting regional dynamics against India, particularly with the potential for a Pakistani military presence in Bangladesh on the grounds of defence cooperation. Such a move would place Pakistan closer to India’s borders along the Northeast, West Bengal, and in the strategically significant Bay of Bengal — a region crucial for India’s economic and military security, as well as for strengthening ties with Southeast Asia. This possibility is especially concerning amid escalating tensions following the April 2025 Pahalgam terror attack, for which New Delhi holds Islamabad accountable. India’s military response in the form of Operation Sindoor and the resulting cross-border shelling has deepened hostilities.

In such a situation, although Chief Advisor Yunus has reiterated Bangladesh’s commitment against terrorism, Dhaka’s growing alignment with Islamabad will remain a cause of apprehension for India. Controversial statements such as the one made by Major General (Retd) ALM Fazlur Rahman, a former Bangladesh Army officer and close aide of Yunus, stating, “If India attacks Pakistan, Bangladesh should occupy the seven states of Northeastern India... I think it is necessary to start discussions with China on a joint military arrangement in this regard,” although made on private social media handles, are unsettling. While the interim government has distanced itself from this remark, Rahman’s position as chairman of the National Independent Commission investigating the 2009 Bangladesh Rifles revolt underscores the need for careful consideration of the statements made by individuals in prominent public roles.

India remains Bangladesh’s largest neighbour, sharing not only contiguous territory and 54 transboundary rivers, but also a history of shared heritage, culture, language and people. Furthermore, the two countries trade in essentials (though this has declined since the regime change in Dhaka) and are mutually dependent on the sustainable use of common resources and the exchange of fundamental services, such as medical tourism. Near the end of the Awami League administration, India and Bangladesh had been exploring the expansion of their defence industrial cooperation. Counter-terrorism formed the bedrock of their defence partnership, and the joint military exercise ‘Sampriti’ was regularly held until its 11th edition in 2023. While given the current circumstances, the advancement of this defence partnership seems remote, consideration for mutual sensitivities is fundamental to a stable neighbourhood policy.

The second question concerns the extent to which an interim government in Bangladesh can legally pursue such strategic shifts. By design, an interim or “caretaker” government with limited authority is primarily entrusted with the responsibility of overseeing elections and ensuring a smooth transition to an elected administration. Further, the legal validity of the interim government, headed by Mohammad Yunus as Chief Adviser, has been repeatedly questioned due to a 2011 Constitutional Amendment Act that abolished the system of non-party caretaker governments in Bangladesh. Although the High Court Division of the Bangladesh Supreme Court has recently “partially annulled the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution and reinstated the non-partisan, neutral caretaker government system”, legalising the Yunus administration, it remains a non-elected government. Therefore, conflicting views concerning the limits to the interim government’s authority and whether its policy directives represent the views of the Bangladeshi populace exist.

The Bangladesh interim government’s emerging foreign policy reflects a conscious departure from decades of strategic regional balancing. Its growing military alignment with Pakistan, alongside increasing divergence from India, signals a potential shift with far-reaching implications for South Asian security, especially amid deepening India-Pakistan hostilities. It is crucial to watch how New Delhi and Islamabad fit into Bangladesh’s changing narrative of national interests and how these countries respond. As the region grapples with rising tensions, Bangladesh’s foreign policy choices and strategic defence posture will play a critical role in shaping the broader trajectory of peace and power dynamics in South Asia.

Sohini Bose is an Associate Fellow with the Strategic Studies Programme at the Observer Research Foundation. Her area of research is India’s eastern maritime neighbourhood, where she explores connectivity, geopolitics and security concerns in the Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea.