The Yuan’s Turning Point

For years, the prevailing wisdom among China watchers has been that Beijing would never tolerate a meaningful appreciation of the yuan. The logic was straightforward: China’s domestic economy remains weak, and exports—supported by a competitively priced currency—are essential to sustaining growth.

George Magnus captured this view succinctly when he observed that China’s post-Covid export boom was less a sign of strength than a reflection of weak domestic demand and Beijing’s inability or unwillingness to address it. As a result, even though the dollar–yuan exchange rate had moved modestly, the renminbi was widely seen as structurally weak—and expected to remain so.

The data appeared to support this belief. Net exports have contributed roughly one-third of China’s reported growth in each of the past two years, and possibly more, given widespread suspicions that other components of growth—especially consumption and investment—are overstated.

The Limits of Export-Driven Growth

A second strand of conventional thinking held that China could not continue generating so much growth from exports indefinitely. If it did, many argued, the global trading system—already under severe strain due to Trump-era trade policies—would simply break. French President Emmanuel Macron voiced this concern bluntly when he warned that global trade imbalances were becoming “unbearable.”

For a time, these concerns did not translate into meaningful pressure on China’s exchange-rate policy. The U.S. Treasury, under Secretary Scott Bessent, remained relatively passive on currency issues. But that complacency is unlikely to persist.

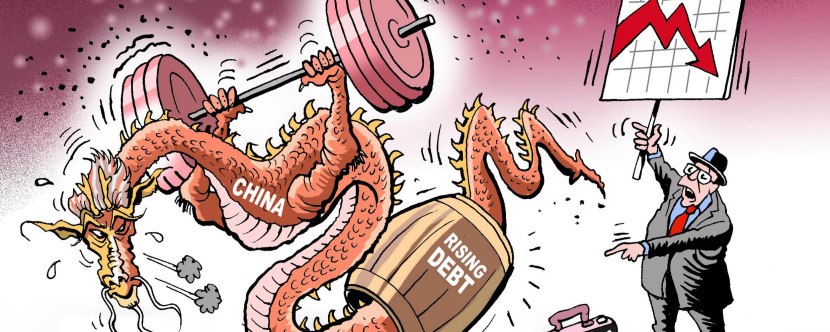

An immovable object—China’s commitment to maintaining broad yuan stability—is now colliding with a potentially unstoppable political force: the growing unwillingness of China’s trading partners to absorb an ever-expanding Chinese export surplus.

If Beijing limits nominal appreciation to just a few percentage points—roughly matching interest-rate differentials to discourage speculation—the real exchange rate will barely move. And if the real effective exchange rate remains at its current depreciated level, China will continue to gain global market share, intensifying trade frictions.

A Shift in Global Perception

What has changed is that China’s exchange rate is no longer being ignored—neither by the International Monetary Fund nor by foreign-exchange markets.

There is now broad acceptance that the yuan is significantly undervalued, and that this undervaluation has played a major role in China’s export outperformance. IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva’s recent comments following the IMF mission to China reflect this shift. That was not the case a year ago. The IMF’s 2024 staff report on China stands as a near-perfect snapshot of the older consensus.

Today, concern about China’s trade surplus is widespread and growing. Economists such as Paul Krugman argue that the true size of the surplus cannot be captured solely by the reported current-account balance. While the official surplus may approach $700 billion in 2025—already enormous—the underlying surplus is likely closer to $1 trillion.

Emerging Market Pressure for Appreciation

Alongside this reassessment of China’s external position is a growing recognition that the yuan is now under appreciation pressure.

Goldman Sachs’ call for a significant yuan appreciation in 2025 both reflects this changing sentiment and has helped reinforce it. Until recently, the dominant narrative was that depreciation pressure prevailed. Some within the IMF reportedly still hold that view, despite clear signals from foreign-exchange settlement data.

Those signals are difficult to ignore. Since June, settlement data show net foreign-exchange purchases averaging around $30 billion per month. There are strong indications—reinforced by persistent Bloomberg reports of state-bank activity—that December’s figures will be significantly higher than those of October and November.

In response, Chinese authorities have intensified efforts to signal that the yuan is not a one-way bet, discouraging investors from piling into the currency.

China’s Core Exchange-Rate Dilemma

This brings us to the heart of China’s exchange-rate challenge.

For most of the past few years, interest-rate differentials favored the dollar. Combined with the yuan’s 2022 depreciation, China’s prolonged domestic slowdown, and recurring tariff threats, these factors drove sustained private capital outflows that offset China’s growing trade surplus.

That balance has now shifted. Private outflows are no longer sufficient to absorb the surplus. As the yuan has begun to inch higher against the dollar, China’s state banks have resumed accumulating foreign assets.

The scale of this accumulation—roughly $300 billion annually—is large in absolute terms but still modest relative to China’s economy. Even if treated as a form of “backdoor” currency intervention, it would remain just below the U.S. Treasury’s 2 percent of GDP threshold for identifying manipulation.

However, keeping state-bank accumulation at this level is becoming increasingly difficult. The underlying trade surplus now far exceeds recent foreign-asset accumulation, leaving ample room for appreciation pressure to intensify if capital-flow dynamics change.

Latent Demand and the Risk of Momentum

If markets conclude that the yuan will appreciate slowly but steadily—with a small chance of a sharper move—it becomes rational for exporters and currency traders to bet on appreciation.

Here, Stephen Jen’s argument is especially relevant. Chinese firms accumulated substantial dollar holdings over the past five years. If appreciation becomes gradual, predictable, and credible, much of that offshore liquidity could return home—adding to appreciation pressure.

In short, China’s foreign-exchange management is becoming “interesting” again.

Policy Trade-Offs and Strategic Choices

Limiting nominal appreciation to 2–3 percent—below the interest-rate differential—may curb speculation, but it will not correct the yuan’s real undervaluation. The resulting expansion of China’s surplus would almost certainly provoke a stronger trade response from its partners.

Conversely, allowing faster appreciation risks pulling offshore capital back into China, increasing volatility. Ironically, maintaining control under such conditions would require more—not less—intervention.

These dilemmas are not new. China has faced them before. But old slogans and warnings against one-way bets are unlikely to suffice this time.

Beijing will need to make fundamental choices—choices that recognize that the yuan can no longer remain structurally weak without triggering economic and political consequences abroad. The era in which China’s exchange rate could be managed quietly, on its own terms, is coming to an end.

(The original article was published by the Council on Foreign Relations under the title “China’s Currency Is Now Facing Substantial

Appreciation Pressure.” This version is a curated adaptation of that article.)